A major factor that influences all performers [at all levels] throughout their sporting careers is the quality and appropriateness of the coaching environment (Martindale et al., 2005, p.353). Against the background of significant concerns about the quality and appropriateness of the contemporary youth sport experience the International Olympic Committee (IOC) recently presented a critical evaluation of the current state of science and practice of youth athlete development. The consensus statement called for a more evidence-informed approach to youth athlete development through the adoption of viable, evidence-informed and inclusive frameworks of athlete development that are flexible (using ‘best practice’ for each developmental level), while embracing individual athlete progression and appropriately responding to the athlete’s perspective and needs (IOC, 2015).

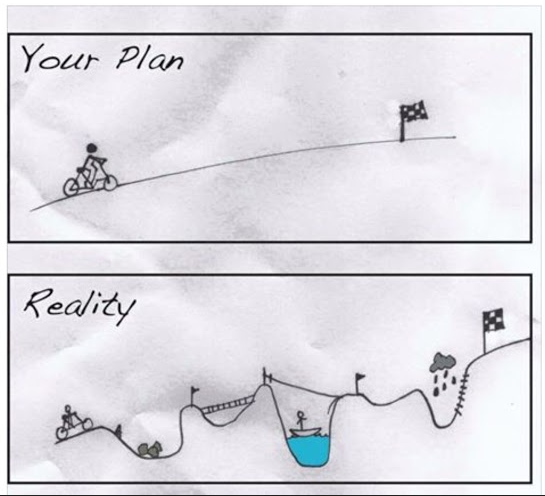

Despite the research literature on athlete development being generally more humanistic and developmentally orientated (e.g. Côté & Lidor, 2013a) there is continuing emergence of non-flexible programmes promoting early talent identification and specialisation often characterised by selection and deselection through all ages and stages (Güllich, A., 2013) with a clear absence of critical thinking (see here). We may know what we are looking for but do we understand what we are looking at?(see here) There is a fundamental flaw in any youth sports system that does not take into account the complexity and non-linearity of human development. For example; sub-systems of the human body develop at different levels and may act as rate limiters on performance (e.g., psychological (Collins & MacNamara, 2012), and social development (Deci & Ryan, 2000).

Predicting the future behaviour of a complex system (young player, team) can be quite futile. Recently, in his book “No hunger in Paradise” Michale Calvin reported that of the 1.5 million children playing organised youth football in the UK only 180 will play in the Premier League. Clearly one should not shape and form children’s football around small numbers. Clearly one should not shape and form children’s football around a system that verifies its existence through survivorship bias.

There is increasing acceptance that individual differences among learners need to be accounted for when coaches plan teaching interventions in any learning contexts (Chow & Atencio, 2012). Learning a sports skill is a complex process that involves a multitude of factors. At the level of the learner, every individual is unique with differences in characteristics such as genetic composition, social-economic backgrounds, prior experiences (Thelen E, Smith LB, Karmiloff-Smith A, Johnson MH (1994). For the young learner, the game, learning the game and the culture of the game is a continuum of complexity. “The coach needs to understand the game but also other aspects that surround the game. The surrounding environment, society, culture, economy” – Joan Vila (Head of Methodology, FC Barcelona).

In this respect, talent is not defined by a young athlete’s fixed set of genetic or acquired components, but should be understood as a dynamically varying relationship captured by the constraints imposed by the tasks experienced, the physical and social environment, and the personal resources of a performer (Araújo & Davids, 2011)

Clearly there is a need for a model and principles that reflect the needs and meets the desire to create a holistic understanding of the sports coaching process and a fuller understanding of its complexity (Jones et al., 2002; Trudel and Gilbert, 2006). Since 1994, a constraints-based framework (see here), (incorporating key ideas from ecological psychology, dynamical systems theory, evolutionary biology and the complexity sciences), has informed the way that many sport scientists seek to understand performance, learning design and the development of expertise and talent in sport (Davids, Handford & Williams, 1994; Williams, Davids & Williams, 1999; Davids et al., 2006; Araújo, & Davids, 2011b; Passos et al., 2016; Seifert et al., 2014). An important feature of the contribution of the constraints-based framework to enhancing understanding of theory and application in the acquisition of skill and expertise in sport is a focus on enhancing the quality of practice in developmental and elite sport (Chow et al., 2016).

A key challenge for coaches is to cater for this abundance of individual characteristics during practice. Therefore, nonlinear pedagogy (grounded in the constraints-led approach) is particularly appealing in that it underpins a learner centred approach and the emergence of skills (Renshaw., 2012). Nonlinear pedagogy provides an appropriate framework for practitioners to cater for individual complexities and dynamic learning environments (Lee, M. C., Chow, J. Y., Komar, J., Tan, C. W., & Button, C.,2014). Training should be designed to encourage the interaction of the different capacities and systems of the young player to help them learn to adapt and develop the ability to learn how to organise their capacities and structures. Seirullo (2002) refers to as this type of training design as “prioritised” rather than “hierarchised.” where the young learner is a participant in the learning process as opposed to being a recipient. England Rugby coach Eddie Jones in a recent interview with the Telegraph newspaper makes a reference to this – “Professional sport to a large extent is educating players to be a recipient and it’s our great belief that to be a World Cup-winning team you need to be a participant.”

Mercé et al. (2007) suggested that football be understood as a “situational sport”. The dynamic of the game comes from unstable situations and big uncertainty caused by teammate’s and opponent behaviours, path of the ball, environment, etc. It is characterised by individual and collective decision making where the player/team adapts performance to each punctual moment. The emerging relationships with teammates and interaction with opponents develops an interesting dialogue (co-adaptability/ interdependence) and an astute coach will observe, reflect and use this dialogue to design a learning space (see here). The learning environment should offer possibilities for “football inter-actions” to the young player independent of their changing abilities needs and concerns.

However, sports coaching research “needs to extend its physical and intellectual boundaries” (Potrac et al., 2007, p.34). There is a limited amount of research undertaken in the integration of theory, science & knowledge from the perspective of high quality applied practice in sport.

This theory- practice gap possibly can be attributed to: “the professional wants new solutions to operational problems while the researcher seeks new knowledge” (Bates, 2002b, p.404). We can refine the literature by accessing the ‘often missing voice’, those whose job it is to implement the ‘theoretical’ models into ‘live’ programmes; i.e., the coaches. Coaches’ experiential knowledge can provide insights beyond those found in traditional empirical research studies. The integration of experiential knowledge of coaches with theoretically driven empirical knowledge represents a promising avenue to drive future applied science research and pedagogical practice (Greenwood, Davids, & Renshaw, 2013).

Coaches who are willing to share their evidence-based practice will improve the quality of practical and applied work in sport. We need to recognise that we probably do not know as much as we think and there is a need to facilitate a space for exchange and learning in a community of practitioners and researchers in order to develop understanding and knowledge and propose improvements for the constructive transformation and evolution of both the coaching environment (practice and coach education) and the literature.

References

Araújo, D., & Davids, K. (2011). What exactly is acquired during skill acquisition? Journal of Consciousness Studies, 18, 723.

Araújo, D., Davids, K., & Hristovski, R. (2006). The ecological dynamics of decision making in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise,7(6), 653-676. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.07.002

Baker, J. (2017). Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Bergeron, M. F., Mountjoy, M., Armstrong, N., Chia, M., Côté, J., Emery, C. A., . . . Engebretsen, L. (2015). International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development. British Journal of Sports Medicine,49(13), 843-851. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094962

Bush, A. (2014). Sports coaching research: context, consequences, and consciousness. New York: Routledge.

Chow, J.-Y., Davids, K., Button, C. & Renshaw, I. (2016). Nonlinear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition: An Introduction. Routledge: London

Collins, D., & Macnamara, Á. (2012). The Rocky Road to the Top. Sports Medicine,42(11), 907-914. doi:10.2165/11635140-000000000-00000

Côté, J., & Lidor, R. (2013). Conditions of children’s talent development in sport. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information on Technology.

Greenwood, D., Davids, K., & Renshaw, I. (2013). Experiential knowledge of expert coaches can help identify informational constraints on performance of dynamic interceptive actions. Journal of Sports Sciences,32(4), 328-335. doi:10.1080/02640414.2013.824599

Güllich, A. (2013). Selection, de-selection and progression in German football talent promotion. European Journal of Sport Science,14(6), 530-537. doi:10.1080/17461391.2013.858371

Jones, R.L., Armour, K.M. and Potrac, P. (2002). Understanding the coaching pro- cess: a framework for social analysis. Quest, 54, 34–48.

Lee, M. C., Chow, J. Y., Komar, J., Tan, C. W., & Button, C. (2014). Nonlinear Pedagogy: An Effective Approach to Cater for Individual Differences in Learning a Sports Skill. PLoS ONE,9(8). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104744

Mallo, J. (2015). Complex Football: From Seirul·los structured training to Frades tactical periodisation. Madrid: Verlag nicht ermittelbar.

Mercé, J., Mundina, J., García, R., Yagüe, J. M., & González, L.-M. (2007). Estudio de un modelo para los procesos cognitivos en jugadores de fútbol de edades comprendidas entre 8 y 12 años. EFDeportes. Revista Digital

Potrac, P., Jones, R.L. and Cushion, C. (2007). Understanding power and the coach’s role in professional English soccer: a preliminary investigation of coach behaviour. Soccer and Society, 8(1), 33–49.

Renshaw, I. (2012). Nonlinear Pedagogy Underpins Intrinsic Motivation in Sports Coaching. The Open Sports Sciences Journal,5(1), 88-99. doi:10.2174/1875399×01205010088

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist,55(1), 68-78. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

Thelen E, Smith LB, Karmiloff-Smith A, Johnson MH (1994) A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action: MIT Press.